Learning Concurrency in Golang

I wanted to learn a new language, so after trying some, I ended up with Golang as one of my favorites for its simplicity and capabilities. It has features I haven’t used in years, like multithreading and concurrency.

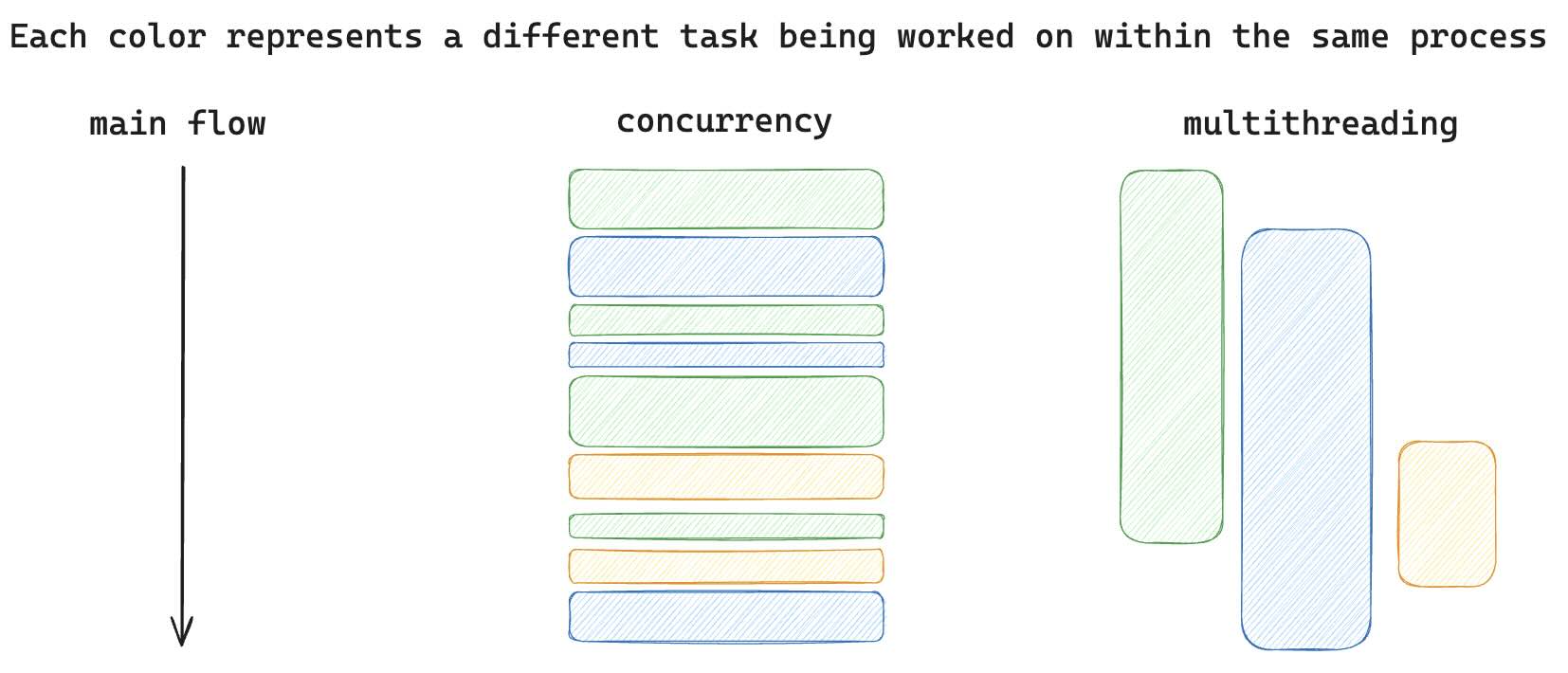

Golang (or Go) supports concurrency through lightweight threads called goroutines. These are different from traditional multithreading—like in Java, where you have to handle sync and coordination to manage shared resources safely. In contrast, Go’s goroutines are lightweight, managed by the Go runtime, and cheaper to create and manage.

While parallelism is doing several things simultaneously, concurrency is about dealing with several things at the same time. When we talk about concurrency and parallelism, we don’t know the order of things. We don’t know what’s going to happen first or what’s going to end first. There is an undefined order of execution.

Imagine you cooking: preparing a soup, a salad and an omelet. You would be one single unit, but you are preparing different dishes. You might finish the salad first or the soup or the omelet… We cannot guarantee that! This would be concurrency, as you are alone dealing with several things. As soon as your partner comes and helps you cook, then we will be talking about parallelism.

I remember building a similar game in Java when I was learning multithreading ten years ago… let’s use this opportunity to do it again with modern Go.

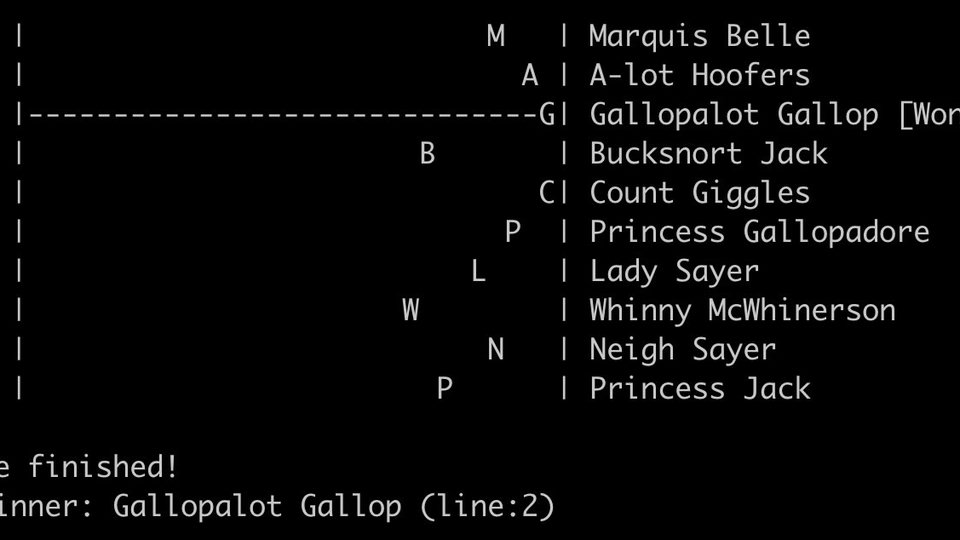

I built a terminal game emulator that mimics one horse racing. Each horse is a goroutine that runs in a shared bidimensional matrix. Once a horse reaches the end, it notifies the shared channel between all other horses –running in different processes– and they all stop, showing in the terminal the winner of the race.

I separated the code into four areas to help visualize it:

- Entry point

- Generating the board

- Rendering the game

- Moving the horses

Entry point

The struct Horse represents each Horse in the race.

The game consists of a list of lines, in which each Horse is running.

type Horse struct {

Name string // The name of the horse

Line int // The competition line

}

func (h Horse) Letter() string {

return fmt.Sprintf("%c", h.Name[0])

}

func (h Horse) Equals(other *Horse) bool {

return other != nil &&

h.Line == other.Line &&

h.Name == other.Name

}

func (h Horse) String() string {

return fmt.Sprintf("%s (line:%d)", h.Name, h.Line)

}You can spawn a new process using the keyword go when invoking any function.

In this game, this is used 1) to render the game RenderGame() and 2) for each horse’s movement startRuningHorseInLine(). The goal is to keep the “rendering” and “movement logic” working in parallel.

func main() {

const lines, lineLength = 12, 30

board := NewRaceBoard(lines, lineLength)

go RenderGame(board)

winnerChan := make(chan Horse)

for line := range board {

// each horse will be moved in different processes

go startRunningHorseInLine(board, line, winnerChan)

}

// wait until one horse reaches the end

winner := <-winnerChan

// render one last time to ensure the latest board state

RenderRaceBoard(board, &winner)

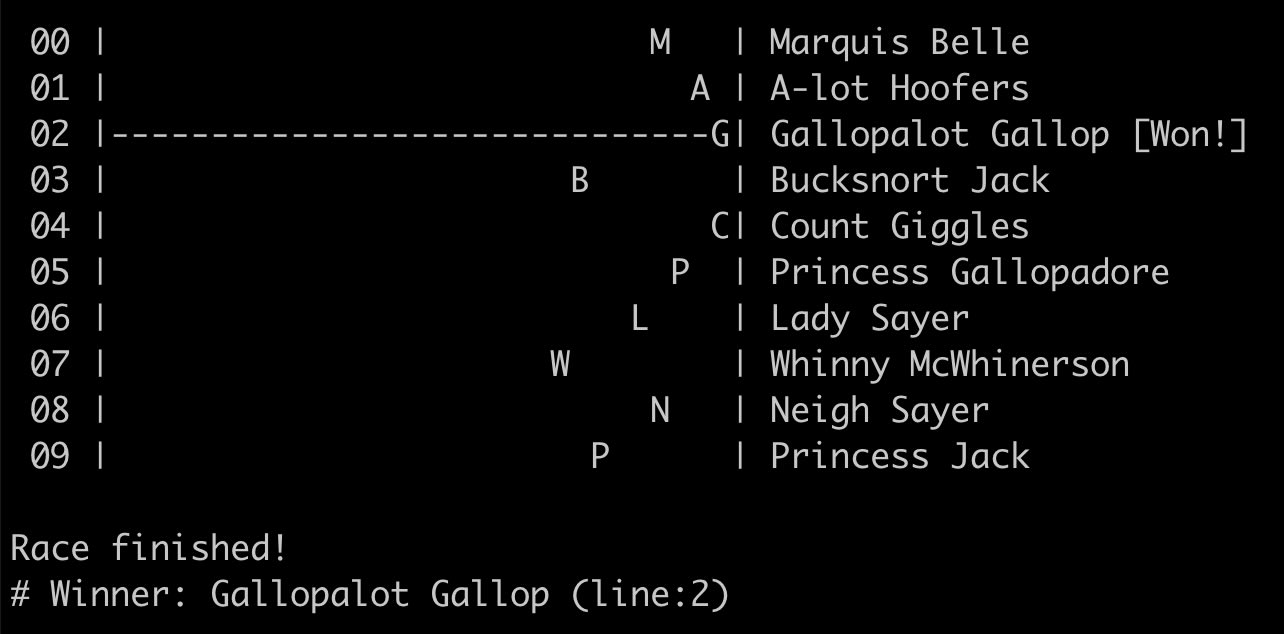

fmt.Println("Race finished!")

fmt.Printf("# Winner: %s\n", winner)

}Generating the board

The race board is a bidimensional matrix of pointers to Horses. Each line “contains” only one Horse; aka only one pointer will point to an actual Horse, the rest will be pointers to nil. During the generation of the Board, we will create one Horse at the first position of each line.

func NewRaceBoard(lines, lineLength int) [][]*Horse {

board := make([][]*Horse, lines)

for line := range board {

board[line] = make([]*Horse, lineLength)

board[line][0] = &Horse{

Name: generateHorseName(),

Line: line,

}

}

return board

}The names are randomly generated using HorseNames.

var HorseNames = [][2]string{

{"Alloping", "Giggles"},

{"A-lot", "Gallop"},

{"BoJack", "Jack"},

{"Baroness", "Belle"},

// ...

}

func generateHorseName() string {

name := HorseNames[rand.Intn(len(HorseNames))][0]

surname := HorseNames[rand.Intn(len(HorseNames))][1]

return name + " " + surname

}Rendering the game

Then RenderGame(), renderRaceBoard(), renderRaceLine() and renderRacePosition() are separated to help focus on each method’s responsibility –identifying what is the subject to be rendered.

RenderGame()is being executed in another process usinggo.

func RenderGame(board [][]*Horse) {

for {

time.Sleep(renderDelay * time.Millisecond)

RenderRaceBoard(board, nil)

}

}

func RenderRaceBoard(board [][]*Horse, winner *Horse) {

// use a "string buffer" to save the whole board state

// so we can later use one IO call to render it

var buffer bytes.Buffer

buffer.WriteString("\n")

for line := range board {

renderRaceLine(board, line, &buffer, winner)

}

clearScreen()

fmt.Println(buffer.String())

}

func clearScreen() {

cmd := exec.Command("clear")

cmd.Stdout = os.Stdout

cmd.Run()

}

func renderRaceLine(

board [][]*Horse,

line int,

buffer *bytes.Buffer,

winner *Horse,

) {

buffer.WriteString(fmt.Sprintf(" %.2d | ", line))

var current Horse

for col := range board[line] {

h := renderRacePosition(board, line, col, buffer, winner)

if h != nil {

current = *h

}

}

buffer.WriteString(fmt.Sprintf("| %s", current.Name))

if current.Equals(winner) {

buffer.WriteString(" [Won!]")

}

buffer.WriteString("\n")

}

func renderRacePosition(

board [][]*Horse,

line, col int,

buffer *bytes.Buffer,

winner *Horse,

) *Horse {

if board[line][col] == nil {

buffer.WriteString(" ")

return nil

}

current := board[line][col]

if current.Equals(winner) {

removeChars(buffer, col+1)

for range board[line] {

buffer.WriteString("-")

}

}

buffer.WriteString(current.Letter())

return current

}Moving the horses

In main(...), the winnerChan is a shared channel that will be used by the first Horse reaching the last position in their line.

Each Horse will run a loop until reaching the end of the line OR receiving (via the shared channel winnerChan) the message that another Horse already won the race. Until then, each horse will move independently by randomly sleeping milliseconds before moving to the next position in their line.

startRuningHorseInLine()runs in another process usinggo.

func main() {

//...

winnerChan := make(chan Horse)

for line := range board {

// each horse will be moved in different processes

go startHorseRunning(board, line, winnerChan)

}

// wait until one horse reaches the end

winner := <-winnerChan

//...

}

func startRunningHorseInLine(board [][]*Horse, line int, winnerChan chan Horse) {

for {

select {

case <-winnerChan: // check if another horse finished

return // in such a case, then stop the for loop

default:

time.Sleep(time.Millisecond * time.Duration(rand.Intn(maxSleepDelay)))

moveHorseOnePos(board, line, winnerChan)

}

}

}

func moveHorseOnePos(board [][]*Horse, line int, winnerChan chan Horse) {

cols := len(board[line])

for col := cols - 1; col > 0; col-- {

if board[line][col-1] == nil {

continue

}

// here we identify that there is a horse in

// the following column, so we move it to the

// current column, and we set `nil` the other one

board[line][col] = board[line][col-1]

board[line][col-1] = nil

if col+1 == cols {

winnerChan <- *board[line][col]

}

break

}

}Source code

The code displayed in this post is a simplified version, so if you would like to check the working source, you can do it here: Chemaclass/go-horse-racing.

Thanks to my former Team Lead, Andrei Boar, who helped me review my first original solution and provided an alternative solution (simpler and better!), which I applied to my original code. The main learning was using a

chan Horseto pass the winner Horse frommain(), instead of using achan booland async.WaitGroupbetween all threads.